I am an avid student of history–not just Western history, but global history. So I ran into two “arguments” about the coronavirus (if it can be dignified with the word) that caused me a great deal of amusement. The first basically went like this:

The flu kills more people in the US every year than the COVID19 coronavirus does. Therefore, people who want an quarantine to prevent the spread of COVID19 coronavirus are actually just racist against Chinese people and are using the false narrative of “dirty foreigners” to justify the racist thing they’ve wanted to do all along.

The second argument evolved from the first and is even more peculiar:

All the concern about COVID19, SARS, and Avian Influenza represents a racist conspiracy against China, falsely portraying it as an epicenter for disease.

Now, the first “argument” is just a Chinese Communist Party propaganda talking point, obediently recycled by the brainless woke leftists who would also argue simultaneously and with a straight face that the diseases introduced to the New World by Europeans constituted an act of genocide. Ironically, two of the three big recorded plagues that devastated Native American populations matched no extant European disease at all and were, instead, almost certainly local diseases, already endemic to the area. The third could have been either local or imported, since the bacteria is widespread, but the culture and medical practices of the Indians made them extremely susceptible to it once they changed their settlement patterns to trade with Europeans, while Europeans were practically immune. Smallpox, with its fatality rate of ten percent for everyone, regardless of ancestry, was not among these devastating diseases.

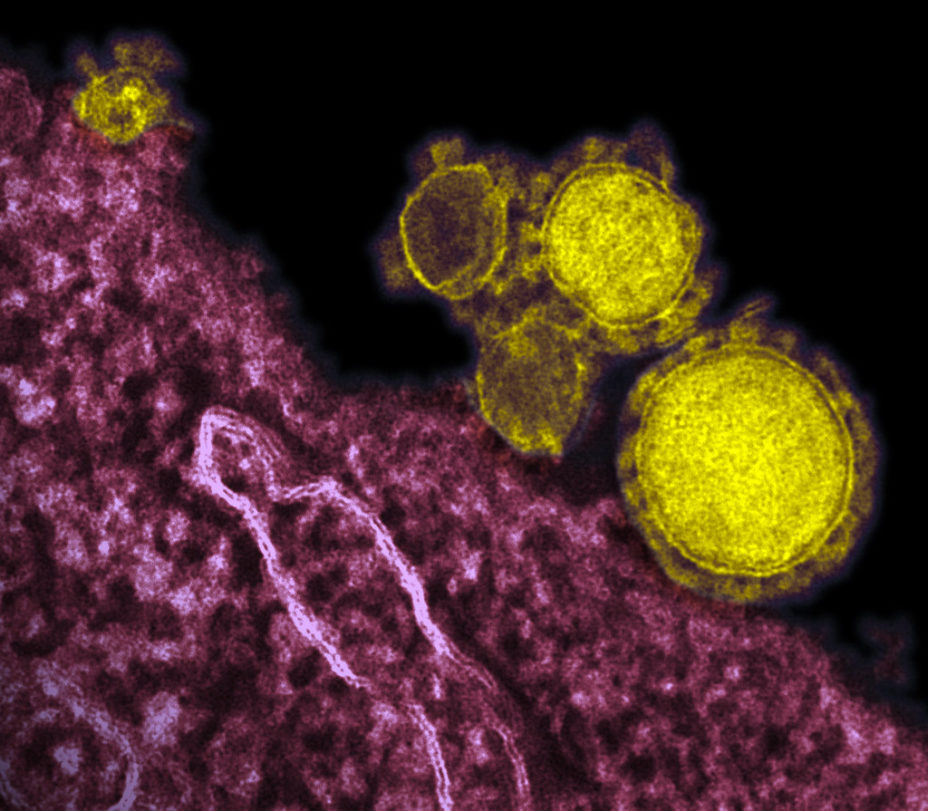

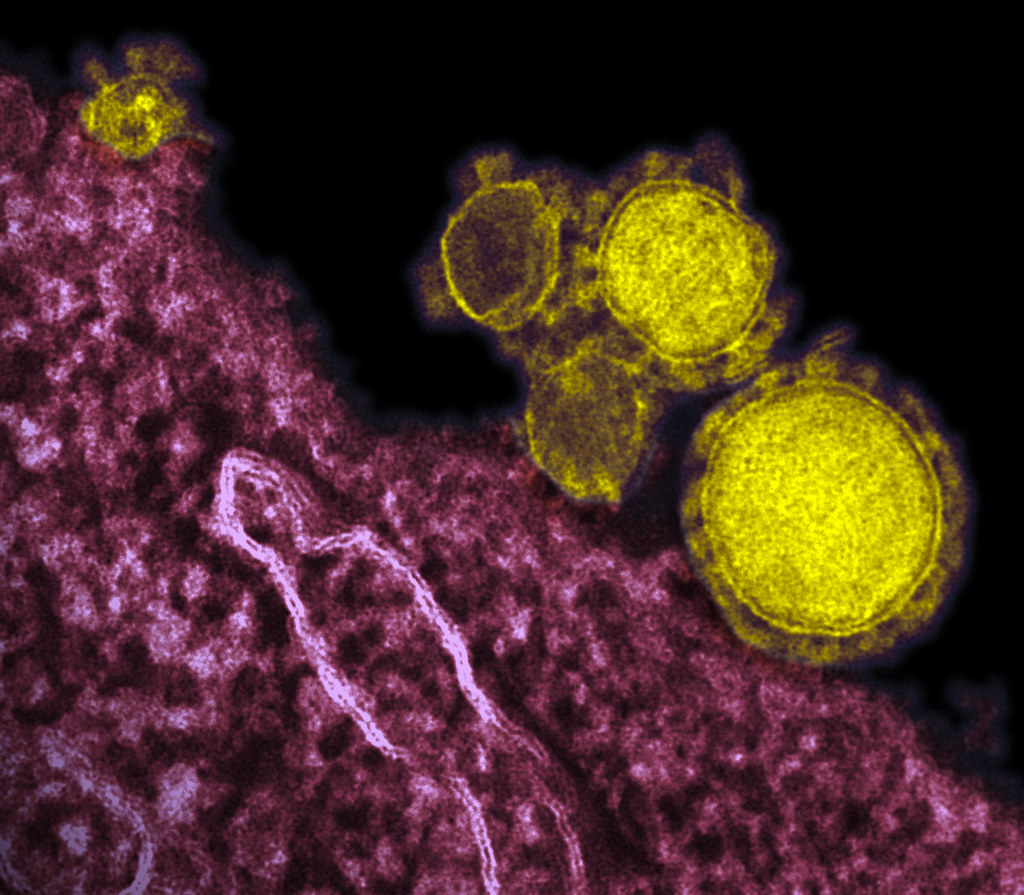

COVID19 has between a 1.5% and a 10% mortality rate, while the seasonal flu gets lumped with all cases of pneumonia (which is a much more common cause of death) and only causes death in .16% of cases. So, yes, a novel disease with a minimum death rate 10 times higher than that of flu is cause for concern, and there is nothing racist about it.

The second “argument” struck me, as a student of history, as particularly funny, because a number of the most devastating plagues in history came from China–all probably different strains of the same disease. (Not smallpox! Smallpox came from India.)

The Plagues from China

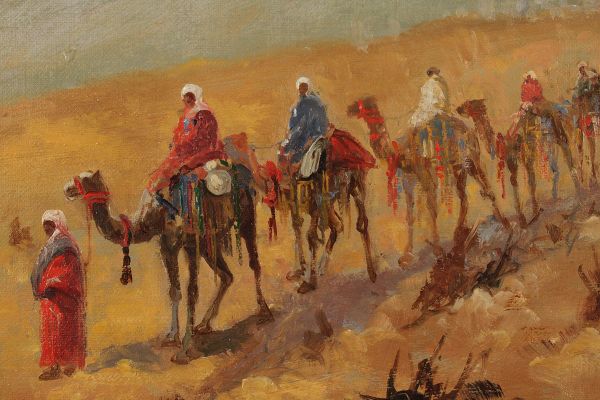

The first was the Antonine Plague. This was probably a close relative of our old friend the Bubonic Plague (caused by the bacteria Yersinia pestis), though it hasn’t been sequenced yet, and it emerged in China around AD 165 and then spread to Parthian Persia along the Silk Road and was picked up by Roman soldiers during the siege of Seleucia. They carried it back to all the major cities of the Roman empire, causing mass death that helped end the Western Roman Empire. This plague is traced by historical records rather than DNA.

The second plague with a documented Chinese origin was the Plague of Justinian. DNA sequencing confirms that it was caused by Yesinia pestis and that the cousin of this strain is found today in the Tian Shan Mountains on the border of, yes, China, along the Silk Road route again. (That doesn’t mean that the strain originated there. Another study based on genetic clock data places the origin of the outbreak securely in China itself.) This plague was the root cause of the success of Islam against the kingdoms of the Sassanids and the Byzantines.

The first place that the Justinian Plague was recorded was in Egypt, so there are two possibilities: either it was introduced quickly from China into Egypt, or else the Antonine Plague had found a reservoir in the Great Lakes region of Africa, from which it spread out multiple times.

I favor the latter theory and believe the Plague of Cyprian (for which no DNA sequencing exists) also belongs to this group. The timeline would go like this: Plague emerges in Han China ca. AD 165. It spreads along the Silk Road, infecting local fleas with this strain, and to Parthia and the Roman Empire and causes the Antonine Plague (ca. 165-180) and forms a reservoir in Ethiopia. This was the cause of the Plague of Cyprian (AD 249-262), which began in Ethiopia, and also the Justinian Plague (541-542, with continued outbreaks through the 570s).

The next major plague was, of course, the Black Death, a different strain of our old enemy Yersinis pestis once again, the deadliest disease to hit Europe for a thousand years, and it shows a Chinese origin once again through DNA sequencing. This freshly imported strain tore through Europe and devastated it repeatedly from 1347 until 1666, killing 30 to 60% of the population and killing up to 450 million people over the centuries until it finally died out. It also affected the Islamic Empire, but how much is not well known, as the state of research into Islamic history is still poor. While personal hygiene was arguably much worse in the Ottoman Empire, where–as recorded in Nukhet Varlik‘s book–people who did not have fleas or lice were suspected as being sick and where Muhammad’s practice actively discouraged the washing of hands after eating except by licking the fingers, yet the practice of extreme female isolation could have provided a natural permanent quarantine of a sort that other nations did not have.

Ironically, European disease prevention measures are the source of the myth that Medieval Europeans were “dirty” because public baths proved to provide the perfect environment for the spread of the disease, and so they were all shut down. People continued taking very regular sponge baths, of course, but routine soaking baths, where the entire body was immersed, fell into general disrepute because of the connection between bathhouses and death. (There is a popular belief that Romans, with their baths, were very clean, but in the absence of the germ theory of disease and a way to sanitize water, the baths were a common place to get all kinds of infections.)

The Black Death didn’t just end the unsanitary public bathhouse. It also caused the introduction of other of European disease control measures that are used to this day. The Black Death caused the creation of quarantine (from the word for “forty,” as quarantines were originally forty days), protective clothing, and even primitive disinfection, with merchants refusing to handle money directly in the marketplace and making people drop it into a pot of vinegar instead. This was also the period when a cultural dislike of rodents and insects in the home became a positive loathing, as they were seen as potential disease vectors long before there was any proof. This led to the development of sophisticated traps and poisons to control them. The miasma theory that disease is caused by bad air was wrong but had several positive health impacts, as raw sewage, smelly water, and stinking malarial swamps were understood as threats to public health.

The West fundamentally viewed illness through a Christian lens, which meant that, while there could be a divine origin of a plague as a punishment for something, disease itself must have a rational mechanism of action because God was rational and created a rational and orderly world. The Christian God was not the fount of secret knowledge about health for believers, so human theories of sickness (like the Four Humors) were not understood to be from God, and they might or might not be correct without affecting the sovereignty of God. Therefore, Christian cultures were free to use the evidence of the world and their reason to revise theories of disease transmission.

The final outbreak of the plague affected China itself most heavily. (Records for the death tolls of earlier outbreaks in China are very poor because the doctrine of the Mandate of Heaven caused authorities to underreport deaths, whenever possible, unless the dynasty was immediately overthrown, and then they were over-reported by the next dynasty.) Called the Third Plague Pandemic, it began in 1855 and lasted until the 1950s, when Western antibiotics ended the last reservoirs of the disease in humans. There were still no antibiotics, and the germ theory of disease was a couple of decades from being confirmed, but European quarantine procedures had reached a level of sophistication that it was able to be contained fairly effectively. The plague hit India, but when cases appeared in South Africa and San Francisco, it was quickly contained. Unlike the previous plagues, this strain still required flea bites to transfer the disease to humans, and so it was relatively easy for Western nations to keep it from spreading. Overall, it killed “only” an estimated 15 million people because of its restricted transmission, a tiny sliver of the population compared to the devastation of the plague when a strain mutated to support person-to-person transmission.

Today, the plague is still endemic to China, and a few people get infected every year. In the US, prairie dogs have become the unlikely perfect hosts for the disease, and they also spread it to people every once in a while. Fortunately, deaths are under 100 people per year worldwide because Yersinia pestis is easily treated by antibiotics.

By the ridiculous logic that the people in whom a disease originated are morally responsible for all the consequences of it, the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the rise of Islam are really China’s fault. But that’s not my logic, because that logic is, in a word, stupid.

Why Do Pandemics Come From China?

The next question is, why has China been a major vector for deadly disease, now and in the past?

The best answer is population density, cultural quirks, and sheer chance.

One of the errors that people make when they look for reasons why something happens is that they don’t look for reasons why something doesn’t happen. That is, they assume that only positive causes, not negative barriers, exist. Jared Diamond’s excruciating work, Guns, Germs, and Steel, is a prime example. He entirely ignored the fact that innovative cultures are a human aberration and assumed all cultures would naturally “progress” if given the same toolset. This is, of course, ridiculously untrue, and there are many social features of many societies that make technological progress unlikely or impossible, irrespective of one’s access to anything. His approach is called biological determinism, and it’s simply bad.

I find that it’s very useful to look at why things don’t happen as much as why they do, so that’s the approach I take here.

Why Don’t Many Pandemics Come From the West?

Indo-European culture has its roots in a cattle-and-horse culture, which gave us measles (usually a mild disease), cowpox (a very mild disease), bovine tuberculosis (rarely acquired), and a mild strain of brucellosis. So the favored animals of Indo-Europeans just weren’t very conducive to producing plague-level epidemics. Many Indo-Europeans slept in very close contact with cows and horses for centuries, but these just aren’t animals that have spread many pandemic-level diseases to people. Indo-Europeans got pigs, but pigs were always kept at a distance from the house. They got chickens eventually, but these were also isolated from the living quarters.

Indo-European culture has a very strong taboo against rodents (rats and mice), which provides a measure of protection from certain categories of disease linked to mouse urine and feces and even against Plague, when it isn’t being carried by human-to-human transmission. Indo-European cultures also have taboos against urine and feces being expelled indoors on the kitchen or bedroom floors, even among little children and animals, and also against spitting on the floor indoors. In an age without correct disease theory, the protective nature of these taboos was not known, but they still protected people. Modern people like to imagine that these taboos are just “normal,” but they really aren’t. Most cultures throughout the history of the world have been quite casual about the urine and feces of infants, for instance.

Europeans were (and are) neatniks compared to most cultures. They were obsessed with white linen from at least the Middle Ages, using the UV rays of the sun to effectively bleach sheets and underclothes after washing, which kills a host of parasites and germs. Europeans also developed a culture of cleaning. Old straw mats were regularly thrown out. Pots and utensils were scrubbed after eating, not just indifferently rinsed and reused or not cleaned at all. Tables were scrubbed with sand until they were spotless. Floors were swept regularly, and even dirt floors were sprinkled with water. Even poor people kept away vermin by keeping a swept yard around their houses–hardpacked earth compacted by traffic and a broom until it produces little mud–with a fenced garden at a little distance.

Most things that people believe about “dirty old Europe” just aren’t true. The myth of animal bones thrown into loose rushes spread on the floor of European castles is just that–a myth. I cannot find a single instance of loose straw or rushes on the floor. Instead, every representation of castles show straw and rushes being woven into mats. The sweet-smelling herbs would have been strewn under the mats so they’d smell nice when people walked over them. Medieval Europeans also washed their hands fastidiously before and after eating. While the filth of cities reached a crisis point in the nineteenth century, it wasn’t because Europeans wanted their cities to be filthy. There were regulations from ancient times about the proper disposal of waste. There was never a time that flinging feces or urine from a window was acceptable (or legal!), despite the Hollywood representations of the Middle Ages. There were always a great deal of people employed to keep the cities clean–ash men, rag and bone men, night soil men, rat catchers, street cleaners, and so on. It was simply a massive task that was too expensive for the productivity of society at that time, so until modern waterworks and sewage became affordable due to increased productivity, it was simply impossible to keep up with in the largest cities. (The horse manure crisis makes for fascinating reading.) Ironically, some of the elites who rejected older patterns of fastidiousness as mere “superstitions” actually did become disgustingly filthy during the so-called Age of Reason, but this was an aberration, and other people noted their filth with disgust.

Europe was also generally not very heavily populated when compared to either the Near East or China. It did not have the population to easily support an incredibly deadly new disease. Its endemic epidemic diseases, like dysentery, were usually incredibly ancient in origin (and cannot even with any confidence be localized to Europe) and didn’t require a high population.

Europe was also not tropical, so mosquito-borne diseases couldn’t establish a year-round presence very well.

Though pandemics didn’t arise in Europe, they hit Europe hard after coming from other places. Though Europe had a lot of customs that tended to limit the spread of disease, Europeans were enthusiastic traders, which brought a lot of diseases home.

As a result, Europe, acting as a crossroads of the world, had to deal with disease containment and also developed several theories of disease that caused Westerners to shun disease vectors even before they understood them. The vermin theory of disease focused on the elimination of pests from homes. The miasma theory of disease connected sewage, stagnant water, air pollution, and putrefaction to disease, and also even general dirt, mildew, and so on were suspected. The germ theory of disease, of course, accurately identified germs as the source of most disease and developed steps to get rid of them, from handwashing with soap to antiseptics to better isolation techniques.

Western medicine is a pretty direct result of Western attitudes towards disease management, treatment, and cure, and it has proven incredibly effective in modern times in treating, controlling, and preventing disease. Because these were all Western-origin concepts, the West has had the longest amount of time to adapt to these ideas and has also embraced their meaning most completely.

The Crisis of Moral Relativists

Now, the same people who will claim that all cultures are equal will also claim that these observations about Western culture are “racist” in as much as they reveal that other cultures are not that way, or at least, were not that way, since Westernization has brought sanitation to many parts of the world. Because these people believe that all cultures are equal, and because they nevertheless believe (as Western-influenced moderns) that maintaining a clean living environment is a good thing, they are unable to accept that many cultures don’t view things this way because they’d be required to accept that they’re either wrong about cleaning being good, or they’re wrong about other cultures being just as good! They imagine that they are “moral relativists,” but they aren’t, really. They’re just fuzzy thinkers. I’ve never once met a person who actually behaves in his life like a true moral relativist.

Now, I don’t have this difficulty. Culture is not race. Some cultures are better than others. Additionally, I can understand that even taboos that now can be proven to have a great utility did not necessarily have that evidence in the past. In the Middle Ages, people didn’t know about germs. They washed their hands before and after eating because it was gross not to. That’s a taboo.

I’m also fine with accepting the moral value of taboos for which there is still no provable benefit. I will not eat dog, for instance, and I find it disgusting, but I understand that I feel this way not because of any inherent quality of dogs or because there is something objectively wrong about dog-eating but just because I have a cultural taboo about it. I also won’t eat cane rats for the same reason.

I extend the came courtesy to many taboos of other people, too. I don’t insist that someone who has, say, converted from Hinduism to Christianity must eat beef, or someone who has converted to Christianity from Islam or Judaism must eat pork. If these foods cause them moral horror, they shouldn’t eat them. It’s that simple. People without any sense of moral horror are terrible people.

With that settled, back to the main topic….

Why Do Pandemic Disease Come From China?

In contrast to Europe, China has been densely populated for a much longer time. The most common Chinese meat is pork, and pigs tend to spread more severe, epidemic-like diseases than cattle. China is a materially poor country for its common people and has been for centuries, and so human waste has been traditionally used to feed pigs and fish that are then consumed again by humans, which is a good way to spread disease.

Traditional Chinese society has treated the urination and defecation of small children very casually, adopting open-crotch pants and largely dealing with the messes that were made wherever they happen to occur, inside or outside, without disinfection. There were no ancient taboos against spitting indoors, and the very Western idea of regular cleaning (rather than ceremonial cleaning attached only to significant events) is still not embraced in the countryside.

While Europeans and people from the Middle East have many food taboos that restricts contacts between humans and many types of animal, Chinese Traditional Medicine provides a food role for almost every type of creature that exists. Similarly, China does not have the clear-cut division between pet and pest that has existed in the West since at least the Middle Ages: birds nesting in the rafters of a house is still considered lucky among the country folk, even though they leave droppings on the kitchen floor.

All of these things persist today, to one degree or another–even pig latrines. Even in the city, folk tradition still regards refrigeration with a high degree of suspicion–the safest food is that which was alive moments before you bought it, so you can see how healthy the animal was with your own eyes. Unsanitary animal slaughter at the outdoor meat markets called wet markets was the major cause of the bird flu epidemic. Though live slaughter was banned, the handling of meat–with no refrigeration, no disinfections, and usually no gloves–is hardly any different now than it was 300 years ago, though hoses rather than buckets wash gore into the gutters today. What matters is that the food is fresh–freshly killed, freshly butchered, freshly cooked. Of course, this does not prevent cases of food fraud.

Of course, there is a valid reason that Chinese people view food safety this way. Chinese “face” culture plus the Chinese conception of “cleverness” promote practices that include the deceptive marketing of one type of meat as another, food adulteration, and covering up breeches in whatever sanitation protocols that do exist. The longstanding Chinese restaurant tradition of serving certain animals with heads is part of a culture were proof must be given or else it is assumed that various kinds of shortcuts will be taken. People wash their utensils and bowls with hot water at the table because it’s assumed that this won’t be done well at the back of the restaurant. China is a shame society, and so misrepresentation is the norm, and a Western sense of integrity and social contract culture simply doesn’t exist.

On top of this, to many Chinese people, germ theory is little more than a silly Western superstition, and Chinese religious beliefs about chi and the elements are obviously correct. The plastic-wrapped meats in a Western supermarket look to them like seething vectors of disease. Chinese traditional religion, unlike Western religion, does relate very directly to beliefs about medicine and illness. To embrace Western medicine is to reject Chinese belief about the nature of the world. Most Chinese people maintain an uncomfortable hybrid of the two belief systems which does little to protect them from disease.

Handwashing after using the bathroom is still not common in China. I have never once seen a Chinese bathroom with soap or a Chinese person in China bringing their own soap to use, as I do when I visit there. Even in hospitals, handwashing is not required or common among doctors or nurses.

In the most sophisticated cities, you will still see children defecating and urinating in public facilities, on the floors of malls or on streets, and men especially spit constantly outdoors and blow their noses explosively onto the sidewalk.

Compounding this is the sheer scale of China’s modern super-cities, which support population densities ideal for the epidemic spread of disease, and a high degree of reliance on public transport. If that was not enough, Chinese also have an enormous attraction to crowds and have a cultural desire to be in crowded places–even if the crowd is so great that they are reduced to shuffling along without experiencing anything, the crowd itself is exciting and desirable.

These super-cities also empty out during Chinese New Year, the greatest annual human migration in the world–which is itself the perfect way for disease to travel. Cholera was spread from its origins in Bengal around the world by the annual Hajj to Mecca in the Middle Ages, and diseases are just a happy to hitch a ride on a modern mass migration today.

Even without the New Year madness, China’s relative wealth means that there are a huge number of flights to and from China, making it an international hub of economic and travel activity that connects not only with richer nations but with many poorer ones that are especially vulnerable to disease. The Chinese Communist Party’s attitude toward any news that could appear to look like a loss of the Mandate of Heaven only compounds the danger.

China is hardly the only weak link in the biosecurity of the world, but it is currently uniquely positioned as the single greatest vulnerability for global pandemics for an array of reasons. Have no fear, though–plenty of other countries are only a couple of decades behind! We are entering a new era in the vaccine arms race, one that we had better be ready for, because it’s coming sooner rather than later.